How the British Invented Communism (And Blamed it on the Jews)

|

by Richard Poe Sunday, January 8, 2023 5:22 pm Eastern Time |

Archives 9 Comments |

How the British Invented Globalism, April 27, 2021 How the British Sold Globalism to America, May 5, 2021 How the British Invented Color Revolutions, May 13, 2021 How the British Invented George Soros, June 18, 2021 How Soros Became Voldemort: Noor Bin Ladin Interviews Shadow Party Co-Author, July 21, 2021 How the British Caused the American Civil War, December 31, 2021 Secret History of the Civil War: Noor Bin Ladin Interviews Richard Poe, January 29, 2022 How the British Invented Communism (And Blamed It on the Jews), |

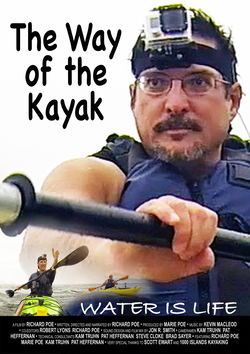

Richard Poe

WAS the Bolshevik Revolution fake? Was Lenin’s 1917 coup little more than a “color revolution,” a staged event, orchestrated by foreign intelligence services? Strong evidence suggests that it was. In the 1920s, prominent Russian exiles accused Great Britain of plotting the Tsar’s downfall. George Buchanan, British ambassador to Russia from 1910 to 1918, devoted 16 pages of his 1923 memoir to denying this charge. But the charge was true. The British secret services had destabilized Russia, just as they had previously destabilized France in 1789. They had infiltrated and weaponized the Bolsheviks, just as they had previously weaponized the Jacobin movement against Louis XVI. While the Tsar was technically Britain’s ally in World War I, British elites feared that a victorious Russia would threaten Britain’s global dominance. Bolshevism provided the solution, demolishing the Tsar’s once-mighty empire, and plunging Russia into chaos and civil war. — RICHARD POE |

“THIS movement among the Jews is not new,” wrote Winston Churchill. “From the days of … Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky… this worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation… has been steadily growing.” (1)

Churchill was talking about communism.

It was February 8, 1920. As Churchill wrote, all eyes were on Russia, where Bolsheviks and anti-Bolsheviks— “Reds” and “Whites”—were battling for control of the country.

Before it was over, some 10 million people would die in the Russian Civil War, mostly civilians, and mostly from disease, famine, and mass atrocities on both sides. From this slaughter, the world’s first communist state would emerge.(2)

Churchill blamed it all on a “worldwide conspiracy” of Jews.

In a full-page article in London’s Illustrated Sunday Herald, Churchill wrote: “There is no need to exaggerate the part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistical Jews. … [T]he majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from the Jewish leaders. … Litvinoff… Trotsky… Zinoviev… Radek—all Jews.”

Churchill declared that the subversive role of “Jewish revolutionaries… in proportion to their number in the population” was “astonishing,” not only in Russia, but throughout Europe.

These Jewish conspirators had now “gripped the Russian people by the hair of their heads,” Churchill said. Unless something was done, many more nations would succumb to what he called “the schemes of the International Jews.”

Churchill Spoke for the British Government

Many readers will be surprised to hear such words from Churchill.

We have been conditioned to think of him as the archnemesis of Hitler and the Nazis, a role he took on later in life. But, in 1920, Churchill’s views were not so different from Hitler’s, at least on certain subjects.

As Secretary of War, Churchill spoke with the full authority of the British government. His article faithfully echoed Britain’s official propaganda of the time.

In April, 1919, the British Foreign Office issued a report called the “Russia No. 1 White Paper: A Collection of Reports on Bolshevism in Russia,” also known as the “Bolshevik Atrocity Bluebook.” It identified Jews as the driving force behind the Tsar’s murder and the Bolshevik Revolution. (3)

The British press followed up with a coordinated, anti-Jewish propaganda campaign, largely based on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document of dubious origin purporting to reveal a Jewish plot to enslave the world.

“Embarrassing Breadcrumb Trail”

The first-ever British edition of The Protocols appeared in February, 1920, under the title The Jewish Peril. Here too, the hand of the British government was evident.

The people involved in producing the book left an “embarrassing breadcrumb trail to the door of the British Establishment,” notes Alan Sarjeant in his 2021 study The Protocols Matrix.(4) Sarjeant concludes that the Jewish Peril was “part of a sophisticated propaganda offensive conceived and financed at the highest levels” of British power.(5)

The translators of The Jewish Peril, George Shanks and Edward G.G. Burdon, were military men with ties to Britain’s war propaganda apparatus.(6)

Its publisher, Eyre & Spottiswoode, was a respected government press entrusted with publishing the King James Bible, the Anglican Prayer Book, and other works owned by the Crown.(7)

The Jewish Peril’s first press run of 30,000 copies exceeded that of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in 1925.(8)

According to Sarjeant, the promotional campaign for The Jewish Peril “was so professionally devised that practically all of Britain’s national and regional newspapers had received a copy for review by the first week of February 1920” —that is, just in time for the splash created by Churchill’s February 8 article.(9)

In the months ahead, leading British newspapers promoted The Jewish Peril.

The London Morning Post ran a lengthy series of articles based on the book. “Read the startling revelations of what is causing the world’s unrest. Read about the evil Jews’ influence,” ran a July 20, 1920 advertisement for the series.(10)

The Times of London went so far as to question whether World War I had been fought against the wrong enemy. “Have we… escaped a ‘Pax Germanica’ only to fall into a ‘Pax Judaica’?” asked a Times editorial of May 8, 1920.(11)

Blame-shifting

Why did the British Establishment turn so suddenly on the Jews?

I believe this was done to provide a scapegoat—a Jewish scapegoat—to deflect from British complicity in the Russian Revolution.

To be clear, Churchill was not wrong when he said Jews were disproportionately represented in the Bolshevik movement. They were. But that was only half the story.(12)

The other half is that the Bolsheviks themselves were pawns in a larger game. A British game.

And Churchill knew that.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that my Grandma and Grandpa—my father’s parents—were Jews, born and raised in the former Russian Empire. They lived through the horrors of the Russian Civil War, and were still experiencing those horrors when Churchill wrote his article in 1920.

I cannot claim perfect objectivity in this matter.

But I do think I can be fair.

I dedicate this small historical correction to the memory of my Grandma and Grandpa, Polina Lazarevna Burde and Rafail Aronovich Pogrebissky, in the hope that these words—long overdue—may help ease their final rest.

The Bolsheviks Had Help

The reality is that the Bolsheviks had no power to overthrow the Russian government nor to defeat the Russian military. Without British help, they could have done neither.

Of all the dirty secrets of the Russian Revolution, this is the dirtiest.

Our story begins with Leon Trotsky.

It was Trotsky who directed the Bolshevik coup of November 7, 1917, and Trotsky who led the Red Army to victory in the Russian Civil War.

Without Trotsky, there would have been no Soviet Union.

But Trotsky did not accomplish these feats on his own. He had help from the British government.

Trotsky’s longstanding ties to British intelligence have never been adequately explained.

Trotsky and British Intelligence

When the Tsar was overthrown on March 15, 1917, Trotsky was working as a journalist in New York City. He set sail for Russia, but British authorities arrested him when his ship stopped in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The British held Trotsky for a month in a Canadian internment camp.

For reasons unknown, Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) came to Trotsky’s rescue, ordering his release. The order came from William Wiseman, US station chief for Britain’s foreign intelligence division, now known as MI6.(13)

Following Trotsky’s release on April 29, 1917, he embarked for Russia and joined the Revolution. The rest is history.(14)

In Russia, British handlers kept Trotsky close. One of his handlers was Clare Sheridan, who happened to be Winston Churchill’s first cousin. She was a sculptress who claimed to be a Bolshevik sympathizer. Sheridan sculpted Trotsky’s portrait, and was rumored to be his lover.(15) Reliable sources have identified Sheridan as a British spy.(16)

Trotsky was banished by Stalin in 1929, spending the rest of his life on the run.

During the Moscow Treason Trials of 1938, Trotsky was convicted, in absentia, of working for the British SIS. The star witness against him was Soviet diplomat Christian Rakovsky, who testified that British intelligence had blackmailed him in London in 1924, using a forged letter, all allegedly with Trotsky’s knowledge and approval.(17)

“I went to Moscow and talked to Trotsky [afterwards],” Rakovsky testified. “Trotsky said that the forged letter was only an excuse. He agreed that we were to work with the British Intelligence.”

Hidden History

Soviet show trials are not the most reliable sources. However, a good deal of independent evidence corroborates Rakovsky’s testimony.

If Rakovsky’s charge is true, then Trotsky was already working for British intelligence as early as 1924. In that case, his relationship with the British was likely established some time earlier, perhaps as early as 1917, when MI6 mysteriously freed him from a Canadian internment camp.

The evidence suggests that Trotsky was already under SIS control in 1920, when Churchill publicly denounced him as a scheming “International Jew.”

Seen in this light, Churchill’s anti-Jewish rant in the Illustrated Sunday Herald begins to look like a cover story.

But covering for what?

What was Churchill trying to hide, by blaming Jews—and Trotsky, in particular—for the Russian Revolution?

You will not find the answer in conventional history books. The story has been erased.

But, in 1920, memories were still fresh. Witnesses were speaking out. The British faced hard questions about their role in the Russian Revolution. They needed a scapegoat.

British Betrayal

Sir George Buchanan, who was British ambassador to Russia from 1910 to 1918, would devote 16 pages of his 1923 memoir to denying that Great Britain had orchestrated the Russian Revolution.(18)

Why did he need to deny this?

The reason is that prominent Russian exiles were accusing Britain of complicity in the Revolution, among them Princess Olga Paley, widow of the Tsar’s uncle Grand Duke Paul.

Paul was the brother of Alexander III, who was Nicholas II’s father.

In the June 1, 1922 Revue de Paris, Princess Paley wrote: “The English Embassy, on orders from [Prime Minister] Lloyd George, had become a hotbed of propaganda. The Liberals, Prince Lvoff, Miliukoff, Rodzianko, Maklakoff, Guchkoff, etc., met there constantly. It was at the English Embassy that it was decided to abandon the legal ways and embark on the path of the Revolution.”(19)

The Princess likewise accused French ambassador Maurice Paléologue of assisting Buchanan in these intrigues, albeit reluctantly. “His position at this period was very delicate,” she wrote. “He [Paléologue] was getting from Paris the most definite orders to support in everything the policy of his English colleague, and yet he realized that this policy was contrary to the interests of France.”(20)

France Subservient to England

Paléologue admits, in his own 1925 memoir, that Buchanan’s collusion with Russian radicals often put the French embassy in an awkward position.“I have been questioned several times about Buchanan’s relations with the liberal parties, and actually asked in all seriousness if he is not secretly working for a revolution,” writes Paléologue in an entry dated December 28, 1916.(21)

Paléologue routinely denied such charges, insisting that Buchanan was a “perfect gentleman” who “would think it an utter disgrace to intrigue against a sovereign to whose court he is accredited.”

In response, a certain Prince Viazemsky once gave Paléologue a “challenging glance” and retorted, “But if his Government has ordered him to encourage our anarchists, he is obliged to do so!”

Paléologue countered, “If his Government ordered him to steal a fork the next time he dines with the Emperor, do you think he would obey?”

Paléologue doubtless understood that, if ordered to do so, his British colleague would not only steal a fork, but every last stick of the Tsar’s silverware.

Nonetheless, with nearly 3 million German troops inching toward Paris, France depended on Britain for her very survival, and was in no position to rock the boat.

Knowledge of British Plans

When Princess Paley identified the British Embassy as the nerve center of the Revolution, she was not just passing along gossip. She had inside knowledge of British operations in Petrograd.

Grand Duke Paul, the Princess’s husband, was deeply involved in the intrigues leading up to the Tsar’s abdication. At every step, he and his royal relatives worked closely with the British Embassy.

His son Dmitri (the Princess’s stepson) was also caught up in British intrigue.

On December 30, 1916, Dmitri took part in the assassination of the “mad monk” Rasputin. For a hundred years, historians have told us this operation was led by Prince Felix Yusupov—a gay, cross-dressing socialite—but all evidence suggests that the real leader was Lieutenant Oswald Rayner, a British intelligence operative who had been Yusupov’s close friend at Oxford.

Rayner was present at the murder scene and is believed to have fired the fatal bullet into Rasputin’s head, according to Andrew Cook’s To Kill Rasputin (2006).(22)

Cook notes that a secret British communication confirmed the killing, stating, “our objective has clearly been achieved. Reaction to the demise of ‘Dark Forces’ has been well-received by all… Rayner is attending to loose ends.”

“Dark Forces” was British code for Rasputin and his cabal of “reactionary” followers at the Russian court.(23)

We can thus see that Princess Paley and her family had rendered many services to the British Crown, even to the point of deceiving their own Sovereign. Despite these services, the Princess and her family were betrayed and abandoned by the British, as indeed all of Russia was betrayed.

Russian liberals like the Grand Duke Paul had been led to believe that Britain would help them establish an enlightened constitutional monarchy in Russia, run on democratic principles. Instead, Russia got five years of civil war, followed by 70 years of communist rule.

In the end, Princess Paley’s husband and her only son were murdered by the Bolsheviks, her husband shot, her son Vladimir thrown down a coal shaft and crushed by logs and stones.(24)

Strange Alliance

“A strange ally, Great Britain,” the Princess mused in her 1924 autobiography Memories of Russia 1916-1919.(25)

In her book, the Princess wonders how Russians could have been fooled into trusting the British, “for, in the history of Russia,” she writes, “the animosity of England traces a red line across three centuries.”

She was right. The Princess correctly notes that Britain struggled for 300 years to stop Russia from attaining what she calls a “free sea” (by which she meant access to warm-water ports). Much blood had been spilled over this.

Bolshevism, the Princess suggests, was just one more weapon deployed by the British to keep Russia weak.

“Is it not to Great Britain that we owe the continuation of the Russian agony?” she asked. “Great Britain supports wittingly… the Government of the Soviets, so as not to allow the real Russia, the National Russia, to come to life again and raise itself up.”

Much evidence suggests that Princess Paley was right.

The Bolsheviks were indeed pawns in a British chess game.

Why Britain Could Not Let Russia Win the War

Although Britain and Russia were technically allies in World War I, the British had more to gain if Russia lost than if she won. This is the dirty secret underlying many mysteries of the Russian Revolution.

In 1915, the Russians were in full retreat, taking heavy losses. The Germans, Austrians, and Turks were advancing on three fronts.

Germany offered Russia a separate peace. Tsar Nicholas was tempted to accept.(26)

But the Allies intervened. They made Nicholas an offer he couldn’t refuse. In March, 1915, they concluded a secret pact with the Tsar, promising to give him Constantinople and the Dardanelles, in the event of an Allied victory.(27)

The Russians accepted. But all evidence suggests the British never intended to keep their promise.

As Princess Paley noted, keeping Russia out of the Mediterranean was a centuries-old British policy. If Russia were allowed to take the Dardanelles now, her warships could challenge British control of the Suez Canal and the trade routes to the East.

No British government in 1915 would have allowed that.

Russian Defeat—a British War Goal?

In her memoir, Princess Paley states that British Prime Minister Lloyd George, “on hearing of the fall of Tsarism in Russia, rubbed his hands together, saying, ‘One of England’s war-aims has been attained!’”(28)

The Princess does not name her source, and the quote is likely apocryphal.

Nonetheless, the story reveals the suspicion many Russians felt, regarding England’s hidden motives.

Some evidence suggests that British leaders really did hope and plan for the defeat of their Russian ally, from the very outset of the war.

This was certainly the attitude of Lord Herbert Kitchener, who served as Secretary of War from August 5, 1914 to his death on June 5, 1916.

In his 1989 book A Peace to End All Peace, US historian David Fromkin notes that Lord Kitchener viewed Russia as a permanent enemy, the only European power capable of challenging British supremacy in Asia. Fromkin writes:

“In Kitchener’s view, Germany was an enemy in Europe and Russia was an enemy in Asia: the paradox of the 1914 war in which Britain and Russia were allied was that by winning in Europe, Britain risked losing in Asia. The only completely satisfactory outcome of the war, from Kitchener’s point of view, was for Germany to lose it without Russia winning it [emphasis added]—and in 1914 it was not clear how that could be accomplished.”(29)

As it happens, the British managed to achieve precisely the result Kitchener sought.

Germany lost the war, but Russia failed to win it.

The Great Game

The British had long experience outwitting and outfoxing Russia. They called it the Great Game.

British intelligence officer Arthur Conolly is said to have coined the term “Great Game” in 1840, to describe the intricate, spy-vs.-spy maneuvers of British and Russian agents vying for advantage in the wastes of Central Asia, as Britain tried desperately to slow Russia’s advance toward India.(30)

However, the Great Game was not just about India, nor did it begin in 1840. It had been going on for centuries.

When English explorers first made contact with Russia in 1553, they found a weak, isolated realm, struggling to drive out the last of the Asiatic warlords who had conquered Russia 300 years earlier.

Mongol and Tatar princes still held the Black Sea coast in 1553, just as they had since the days of Genghis Khan. But now they were vassals of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Turkish Sultan. Russia’s southern coast was under Turkish control. Russian ships could not sail the Black Sea without the Sultan’s permission.

Tsar Ivan IV—known as Ivan the Terrible—welcomed the British traders, at first, but became angry when they demanded a monopoly over Russian trade. For their impudence, Ivan expelled the newly-established British Muscovy Company.(31)

Why England Backed the Turks

Two hundred years later, Russia was no longer weak. The Russian Empress Catherine the Great had finally succeeded in expelling the Turks from the Black Sea shore, after fighting two wars with the Sultan (1768-1774 and 1787-1792).

Catherine’s success set off alarm bells in London.

The Russians now had seaports on the Black Sea, threatening British control of the Mediterranean.

When the Black Sea fortress of Ochakov fell to Russian forces in 1788, the English threatened war, demanding that Catherine return the fortress to the Sultan.

She refused.

The British backed down, dropping their ultimatum, but vowed to stop further Russian expansion.(32)

Their strategy was to play off Muslim against Christian. For the next hundred years, the British propped up the faltering Ottoman Empire, as a counterweight, to keep Russia in check.

The “Greek Plan”

Catherine’s strategy was the opposite of the British.

Instead of pitting Muslim against Christian, Catherine sought to unite Christians in a common cause, to drive the Turks out of Europe.

The Ottomans still ruled a large part of Europe, including Greece and the Balkan nations of Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Albania, Moldova, Kosovo and Macedonia.

Catherine’s plan was to liberate these Christian lands from Muslim rule.

She sought to restore the Byzantine Empire, under the Greek Orthodox faith.

Her grandson Constantine would be crowned Byzantine Emperor.

His capital would be in Constantinople (which Russians affectionately called Tsargrad, City of Caesar).

Catherine called this her “Greek Plan” (Grechesky proyekt).(33)

Russia’s Byzantine Roots

Catherine’s nostalgia for the Byzantine Empire had deep roots in Russian history.

Prior to 988 AD, the Eastern Slavs (ancestors of the Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians) were pagans, worshipping the old Slavic gods.

Vladimir the Great, the Grand Duke of Kiev, converted to Christianity in 988, embracing the Eastern Orthodox faith of the Byzantine Greeks.

Byzantine missionaries devised an alphabet for the Slavs, based on the Greek alphabet, the basis of today’s Cyrillic writing system.

When Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, many Byzantines fled to Russia.

The Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan III, married the Byzantine princess Sophia Paleologa, niece of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine emperor, who died fighting the Turks in the streets of Constantinople.

In honor of the fallen Byzantine Empire, Ivan adopted the Byzantine double-headed eagle as Russia’s coat-of-arms. He gave himself the title “Tsar” (meaning Caesar) and declared Moscow the “Third Rome,” successor of the “Second Rome,” Constantinople, now in Turkish hands.

Thus was the Russian Empire born, like a phoenix, from the ashes of Constantinople.(34)

For these reasons, a bond has always existed between Russia and Greece. The Russians look to Byzantium as their spiritual ancestor, while the Greeks look to Russia as savior and protector.

Why England Opposed the “Greek Plan”

Catherine hoped that her so-called “Greek Plan” would appeal to Christian rulers, be they Catholic or Orthodox.

She secretly proposed it to the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II in 1780.(35)

However, the British had other ideas. They soon learned of Catherine’s plan and resolved to stop it.

The British understood that Catherine’s new Byzantine Empire would be a faithful ally of Russia, sharing the same Orthodox faith.

It would completely replace the old Ottoman Empire, tipping the power balance in Russia’s favor.

The British would no longer be able to play off Turks against Russians, Muslims against Christians. They would face a united front of Orthodox Christians, guarding the gateways to the East.

Even worse for the British, Catherine’s new Byzantine Empire would open the Dardanelles to Russia, giving Russian warships access to the Mediterranean.

Britain would lose control of the Mediterranean and the trade routes to the East.

For these reasons, the British resolved to defeat Catherine’s plan.

The “Eastern Question”

Catherine the Great died in 1796, but her Greek Plan lived on.

England’s opposition to the Greek Plan would ultimately lead to the Russian Revolution.

Throughout the 19th century, British strategists pondered how to keep Russia from taking Constantinople and the Dardanelle Straits. They called it the “Eastern Question.”

Unfortunately for the British, their Turkish ally was growing weaker while the Russians grew stronger. The Ottoman Empire was in long-term decline.

And so the British did a delicate dance, playing off Russian against Turk, Turk against Russian, as the occasion demanded, often switching sides with dizzying suddenness.

Thus, when the Russians instigated a Greek rebellion against the Turks in 1821, the British betrayed their Turkish allies and sided with the Greeks. By this means, the British won the friendship of the new Greek state, and prevented Greece from becoming a Russian dependency.(36)

On the other hand, when the Russians attacked the Turks in 1853, the British sided with the Sultan. French and British armies invaded Russia, defeating her in the Crimean War of 1853-1856.

The peace terms of the Crimean War required Russia to demilitarize the Black Sea. An angry, humiliated Tsar Alexander II was forced to disperse his Black Sea Fleet and destroy his fortifications.(37)

“Dominion of the World”

British strategists of the Victorian era believed the “Eastern Question” would one day determine who ruled the world. In their quest for global dominion, they saw Russia as their chief rival.

As David Fromkin puts it in his aforementioned book A Peace to End All Peace:

“Defeating Russian designs in Asia emerged as the obsessive goal of generations of British civilian and military officials. Their attempt to do so was, for them, ‘the Great Game,’ in which the stakes ran high. George Curzon, the future Viceroy of India, defined the stakes clearly: ‘Turkestan, Afghanistan, Transcaspia, Persia… they are the pieces on a chessboard upon which is being played out a game for the dominion of the world.’ Queen Victoria put it even more clearly: it was, she said, ‘a question of Russian or British supremacy in the world.’”(38)

Queen Victoria took the Great Game very seriously, and was determined to prevail, as her correspondence with Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli reveals.

“People who hardly deserve the name of real Christians”

During the so-called Great Eastern Crisis of 1875-1878, Christian populations rose up in revolt throughout the Ottoman Empire. The Turks suppressed these risings with startling cruelty, slaughtering Christians by the tens of thousands. In Bulgaria alone, as many as 100,000 Christians may have been killed.

Europeans were outraged. At least, most of them were. Queen Victoria, however, defended the Turks.

“It is not the question of upholding Turkey: it is the question of Russian or British supremacy in the world!” she explained in a letter to Disraeli on April 19, 1877.(39)

In Victoria’s view, the only thing that mattered was keeping the Russians out of Constantinople. If that meant abandoning eastern Christians to genocide, so be it.

Russia, on the other hand, decided to rescue the beleaguered Christians, declaring war on the Ottomans on April 24, 1877. A Russian army invaded the Ottoman Empire, marching through Romania and Bulgaria (both under Turkish rule at the time) and advancing on Constantinople.

Queen Victoria wanted the Russians stopped. As for the poor, suffering Christians, they were mostly Eastern Orthodox. Who cared about them anyway?

“This mawkish sentimentality for people who hardly deserve the name of real Christians… is really incomprehensible,” Victoria wrote Disraeli on March 21, 1877.(40)

The eastern Christians were “quite as cruel as the Turks,” Victoria stated on June 27. “Russia is as barbarous and tyrannical as the Turks,” she added. (41)

Victoria’s Wrath

As the Russians advanced on Constantinople, Victoria’s letters to Disraeli grew increasingly frantic.

Referring to herself in the third person, in accordance with the royal custom of the day, Victoria demanded military action, repeatedly threatening to abdicate if Constantinople fell.

“Russia is advancing and will be before Constantinople in no time!” she wrote on June 27. “Then the government will be fearfully blamed and the Queen so humiliated that she thinks she would abdicate at once. Be bold!”(42)

On January 10, 1878, Victoria wrote Disraeli that she could not bear the shame of allowing England to “kiss the feet of the great barbarians [the Russians], the retarders of all liberty and civilisation that exists… Oh, if the Queen were a man, she would like to go and give those Russians, whose word one cannot believe, such a beating!”(43)

Only ten days later, Victoria got her wish.

As the Russians reached the outskirts of Constantinople, the British finally intervened. They warned the Russians to halt, sending a fleet of warships through the Dardanelles to protect the Turkish capital.

Fearful of the British fleet, the Russian army came to a halt at the village of San Stefano, on January 20, 1878, only seven miles from the center of Constantinople.(44)

This was the closest the Russians ever got to their dream of a New Byzantium.

Keeping Russia in the War

Britain’s obsession with the “Eastern Question” remained undiminished at the outset of World War I.

British statesmen were just as determined as ever to keep Russia out of the Straits.

But the situation had changed. The Ottoman Empire was now at war with England. The Turks had made an alliance with Germany on August 2, 1914.

In addition, Russia’s situation had changed.

The Russian army was showing unexpected weakness. In the first month of war, the Germans annihilated two Russian armies, killing as many as 120,000 men.

The Germans offered Russia a separate peace, and the Russians were listening.(45)

Britain scrambled to help her faltering ally, frantic to keep Russia in the war.

On January 1, 1915, Russian commander-in-chief Grand Duke Nicholas (a cousin of the Tsar) requested help from the British. The Turks were hitting the Russians hard in the Caucasus. The Grand Duke asked the British to attack the Ottomans in the West, to relieve pressure on Russian troops in the East.(46)

The British agreed. They had no choice.

If they refused to help, the Russians would make a separate peace with the Central Powers.

The Riddle of Gallipoli

Thus began one of the strangest, most mysterious, episodes of World War I—the Gallipoli Campaign.

In response to the Russian request, the British promised a direct attack on the Dardanelles. If the attack were successful, Constantinople would fall, and the Ottoman Empire with it.

But the attack failed. Catastrophically.(47)

Military historians have spent more than a hundred years trying to figure out why.

On March 18, 1915, an Anglo-French fleet sailed up the narrow, 38-mile Dardanelles channel toward Constantinople. But they were turned back with heavy losses from mines and artillery fire.

On April 25, the Allies tried again, this time with an amphibious assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula (which forms the northern shore of the Straits).

Over an eight-month period, more than 410,000 British and Commonwealth troops—including British, Irish, Australians, New Zealanders, and Indians—would land on the Gallipoli beaches. Nearly 47,000 would die.

About 79,000 French troops also took part in the attack, of whom 9,798 were killed, bringing the total Allied dead to 56,707.

In the end, the attack was abandoned. Allied troops were withdrawn between December 7, 1915 and January 9, 1916.

Winston Churchill was blamed, perhaps unjustly. He was forced to step down as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Bungling or Subterfuge?

Most historians blame the Gallipoli disaster on recklessness and incompetence. However, some suggest that the British deliberately pulled their punches, allowing the Turks to win.

One such is Harvey Broadbent, an Australian historian who has written four books on the Gallipoli Campaign, including The Boys Who Came Home (1990), Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore (2005), Defending Gallipoli (2015), and Gallipoli: The Turkish Defence (2015).

In an April 23, 2009 article titled, “Gallipoli: One Great Deception?” Broadbent hypothesized that the Gallipoli Campaign was never meant to succeed, and may have been “conceived and conducted as a ruse to keep the Russians in the war…”(48)

Broadbent speculates that the purpose of the campaign may have been to provide an illusion that the Allies were speeding to Russia’s rescue, when, in fact, they were not.

The sheer scale and persistence of the alleged “bungling” are difficult to explain by incompetence alone, Broadbent argues, raising the question of deliberate self-sabotage. He writes:

“It… occurred to me that the under-resourcing, informing the enemy five months in advance of the intention to attack, the hurried and inadequate planning, the overly complicated landing plan on exposed and difficult beaches with no initial massive bombardments to pulverise enemy defences, selection of the most incompetent and timid commanders for a difficult operation and apparent constant bungling that characterised the Allied conduct of the campaign may be attributed to something more than ineptitude. … Professor Robin Prior, in his new book, Gallipoli: End of a Myth, lists a series of decisions and events that he describes as puzzling or incomprehensible.”

A Question of Motive

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Broadbent is right. Suppose the Allies deliberately sent nearly 57,000 men to their deaths, with no hope of victory.

What was their motive?

Broadbent points out that, had the Allies succeeded in taking Constantinople and the Straits, they would have been obliged to turn over these prizes to Russia, in accordance with a secret treaty of March 1915.

The Allies would have done all the work, and the Russians reaped the rewards.

“Russia alone, will, if the war is successful, gather the fruits of these operations,” said a March 15, 1915 memorandum of the British Asquith government, quoted by Broadbent.

In short, honoring the treaty would have done nothing for England. On the contrary, it would have harmed British interests by upending “nearly 200 years of British foreign policy which had opposed a Russian presence in the Mediterranean…” Broadbent notes.

Better to leave Constantinople to the Turks, than let the Russians get it.

British strategists calculated that, once the Ottoman Empire was defeated and dismembered, the Straits could be safely entrusted to a “shrunken and compliant Ottoman state,” Broadbent explains.

Such considerations might have led British commanders to conclude that it was better for the attack to fail.

“In war thousands of lives are sacrificed for such grand strategies,” Broadbent notes.

Saved by the Revolution

Plainly, the British would have preferred not to hand over Constantinople to the Russians. But how could they get out of it? Sabotaging the Gallipoli Campaign, in and of itself, would not have achieved this goal.

The secret treaty—known as the Constantinople Agreement—was inescapable. As long as the Allies won the war, Russia would get her prize. The promise was binding, no matter who won at Gallipoli.

Yet the British got off the hook anyway. What saved them was the Russian Revolution, says Broadbent.

“[T]he agreement never had to be honoured…. ,” he writes. “[T]he Bolshevik Government withdrew from the war and all Tzarist agreements including the Gallipoli treaty.”

In short, the Bolsheviks saved the day, by unilaterally withdrawing their claim to Constantinople.

This was a great stroke of luck for the British.

But was it luck? Or was it planning?

Broadbent suggests the latter.

Double-Crossing the Tsar

If the Russian claim to Constantinople was completely unaffected by who won at Gallipoli, then why would the British go to all the trouble of staging a phony attack and making sure they lost (as Broadbent hypothesizes)?

Why not go for the win?

In answer, Broadbent poses a hypothetical question. He asks, “If there had been a victory at Gallipoli would there have been a Russian Revolution?”

Probably not, says Broadbent.

In his opinion, the capture of Constantinople, and its subsequent occupation by Russia, would have caused such an explosion of religious and patriotic fervor in Russia, as to make revolution impossible.

Referring to Catherine the Great’s plan for a New Byzantium, Broadbent writes: “With the ultimate re-establishment of a new Byzantine Empire under the Tzar on the new Christian throne in ‘Tzaragrad’ on the Bosphorus, would the millions of Russian religious peasants, massively influenced by the victory, have flocked to support the Holy Tzar in the face of revolution, thus thwarting the Bolsheviks?”

Broadbent thinks they might have. In that case, the Tsar might have remained on his throne.

Such an outcome would have been contrary to British interests, Broadbent suggests.

Did Gallipoli Cause the Russian Revolution?

From the British standpoint, a Russian victory in World War I would have been catastrophic, Broadbent insists.

It would have meant that the British and Commonwealth troops at Gallipoli were “fighting not for a war to make the world safe for democracy but for the domination of the Slav world by Tzarist Russia.”

Broadbent concludes, “The way out of all this of course was to ensure that Istanbul remained unconquered [emphasis added].”

Lord Kitchener and other high officials of Asquith’s government would have been thinking along the same lines, as they made plans for Gallipoli, Broadbent suggests.

Broadbent’s arguments are weighty. He compels us to consider whether Britain may have deliberately pulled her punches at Gallipoli precisely in order to deprive the Tsar of the one victory that might have saved his throne.

Bargaining Chip

Broadbent’s article leaves an important question unanswered, however. If the March 1915 agreement was so inimical to British interests, why did Britain make such a treaty in the first place?

Why did they offer Constantinople to Russia, if they didn’t want Russia to have it?

Broadbent argues that it was bait to keep Russia in the war. No doubt, this is partly true. But there was another reason as well.

The British did not offer Constantinople to the Russians for free. They asked something in return. Specifically, they demanded a large chunk of the newly-discovered Persian oil fields. The Russians agreed.(49)

In 1907, Russia and Britain had signed a treaty dividing Persia into two spheres of influence, with the Russians in the north, the British in the south, and a large neutral zone in between.

Now, on the eve of the Gallipoli Campaign, the British suddenly asked that the neutral zone be added to the British sphere of influence, greatly enlarging Britain’s share of Persia’s oil-rich territory.

Whatever else we may conclude about the Gallipoli Campaign, it appears to have been a bargaining chip in a high-stakes negotiation over Persian oil.

The Constantinople Agreement was hammered out in a series of diplomatic letters between France, Britain and Russia from March 4 to April 10, 1915. Opinions vary as to when the Agreement actually became operative.

The Encyclopedia Britannica gives the date of March 18, 1915, which happens to be the very day the Allied fleet commenced its attack on the Dardanelles. If true, this would suggest that the British held off their attack until the very moment the agreement was settled.

The Persian oil concession may very well have been the price the British demanded for attacking Constantinople.

Trotsky’s Unexpected Service to the Crown

In the end, the British got much more than the Persian neutral zone. The entire nation of Persia was turned over to Britain, thanks to the unexpected generosity of Leon Trotsky, whose curious connections with British intelligence we have already noted.(50)

Following the Bolshevik coup of November 7, 1917, Trotsky held equal power with Lenin, to the point where discussions took place as to which of them would lead the new government.

“[T]he Lenin-Trotsky combination is all-powerful,” the Times of London reported on November 19, 1917.(51)

In the end, Trotsky took the position of Commissar for Foreign Affairs, on November 8, 1917, the day after the coup. He did this to focus on making a quick peace with Germany.

But then Trotsky did a curious thing. On November 22, he suddenly announced that the Bolshevik government would repudiate all secret treaties and agreements made by previous Russian governments.

Trotsky said the treaties had “lost all their obligatory force for the Russian workmen, soldiers, and peasants, who have taken the government into their own hands…”(52)

“We sweep all secret treaties into the dustbin,” he said.(53)

By publishing and repudiating the treaties, Trotsky claimed he was rejecting “Imperialism, with its dark plans of conquest and its robber alliances.” (54)

What he was actually doing was enriching the greatest imperial power on earth, Great Britain.

British Petroleum and the Bolsheviks

Among the treaties Trotsky repudiated was the secret Constantinople Agreement of March 18, 1915. He released the British unilaterally from their promise to hand over Constantinople and the Straits.(55)

Trotsky likewise repudiated Russia’s extensive interests in Persia, leaving everything for the British.(56)

In August, 1919, the British government took advantage of the Russian withdrawal by claiming all drilling rights in Persia for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. The Persian government never actually agreed to this, but their opinion no longer mattered.(57)

“Russian influence in Persia was reduced to nil and the British… made themselves masters in all of Persia,” wrote US journalist Louis Fischer in his 1926 book Oil Imperialism.(58)

Trotsky’s revolutionary rhetoric notwithstanding, these actions brought no benefit to the Russian people. They helped only the British. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was now free to expand, since its chief rival, the Russian Empire, had suddenly vanished into thin air.

In 1935, the fast-growing British oil giant changed its name to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, then to British Petroleum in 1954.

If Harvey Broadbent is correct—if the British really did pull their punches at Gallipoli to prevent Russia from winning the war—then it appears their ruse was successful, greatly benefitting Britain, at least from a commercial standpoint.

A 150-Year Conspiracy

The British government plainly had much to hide in its relationship with the Bolsheviks, and therefore much to gain by deflecting blame onto others, such as the Jews.

However, Churchill’s 1920 article in the Illustrated Sunday Herald went further. Churchill did not just blame the Jews for the Bolshevik Revolution. He blamed them for literally “every subversive movement during the 19th century.”

Churchill alleged a 150-year conspiracy, dating back to the Bavarian Illuminati of Adam Weishaupt and the French Revolution of 1789. He wrote:

“This movement among the Jews is not new. From the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt to those of Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky… this worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation… has been steadily growing. It played… a definitely recognisable part in the tragedy of the French Revolution. It has been the mainspring of every subversive movement during the 19th century…”(59)

What did Churchill mean by this? Was he simply exaggerating for dramatic effect? Indulging in a bit of rhetorical overkill?

Or was his reference to a 150-year conspiracy purposeful and calculated?

I would say it was calculated.

Churchill’s allegation of a centuries-old conspiracy appears to be yet another cover story, calculated to distract from yet another sensitive subject which the British government had reason to hide.

Britain’s Secret Weapon: Color Revolution

In an earlier article, “How the British Invented Color Revolutions,” I argued that the modern “color revolution” or bloodless coup was perfected by 20th-century British psywar strategists such as Bertrand Russell, Basil Liddell Hart, and Stephen King-Hall.(60)

In that article—published May 14, 2021—I mentioned Portugal’s 1974 Carnation Revolution as the first, full-fledged “color revolution” of which I was aware. Since then, I have learned that color revolutions go back much farther than I had imagined.

The British have been doing it for centuries.

If we define a color revolution as a fake insurrection—that is, as a foreign-sponsored coup masquerading as a people’s uprising—then we must conclude that the French Revolution of 1789 and the Russian Revolutions of 1917 seem to fit that description in many ways.

In both cases, the uprisings began not in the streets, but in the drawing rooms of liberal aristocrats.

In both cases, the hidden hand of British intelligence can be found manipulating events behind the scenes.

In both cases, “team colors” were used to identify the rebels, in a manner similar to today’s color revolutions— specifically, the tricolor cockade and “Phrygian” cap of the French Revolution, and the red flag and “Scythian” cap of the Bolsheviks.

It seems more than coincidental that the Age of Revolution coincided with Britain’s rise to global dominance. It was precisely during that era—the late 18th to early 20th centuries—that Britain mastered the use of political subversion as a weapon of statecraft, an instrument for toppling governments that stood in her way.

Removing Louis XVI

King Louis XVI was Britain’s number one enemy when the French Revolution broke out. He had earned Britain’s hatred by intervening in the American Revolution, forcing Britain to grant independence to the Thirteen Colonies.

The British never forgave him. They devised a plan for Louis’s removal.

They did not have to wait long for their revenge. The growing demand for liberal reform in France provided an opening.

Inspired by America’s revolution, many in France hoped for a better world, in which rank and privilege would give way to liberty and equality.

French liberals of that time tended to be Anglophilic. They viewed England and America alike as beacons of hope, sharing a common tradition of English liberty.(61)

The British secret services took advantage of this good will.

Intelligence operatives posing as English reformers infiltrated the French intelligentsia, pushing French dissidents toward violence, class warfare, and hatred of the Bourbon dynasty.

The Revolution Hijacked

No less an authority than Thomas Jefferson accused the British of using “hired” agents of influence to subvert the French Revolution. Jefferson was in a position to know, as he had been US ambassador to France when the Revolution broke out in 1789.

Jefferson and Lafayette had hoped the uprising would bring constitutional monarchy to France, leaving Louis XVI safely on his throne. But this was not to be.

In a letter of February 14, 1815, Jefferson wrote Lafayette, lamenting the failure of the French Revolution, and blaming it on British intrigue.(62)

The British had subverted the Revolution, Jefferson wrote, by sending “hired pretenders” to “crush in their own councils the genuine republicans,” thus turning the Revolution toward “destruction” and the “unprincipled and bloody tyranny of Robespierre…”

By such means, wrote Jefferson, “the foreigner” overthrew “by gold the government he could not overthrow by arms” — as apt a description of a color revolution as one could imagine.

Paid Agents

Jefferson expressed the same view in a letter of January 31, 1815 to William Plumer, a New Hampshire lawyer and politician.(63)

“[W]hen England took alarm lest France, become republican, should recover energies dangerous to her,” wrote Jefferson, “she employed emissaries with means to engage incendiaries and anarchists in the disorganisation of all government there…”

According to Jefferson, these hired “incendiaries and anarchists” infiltrated the Revolution by “assuming exaggerated zeal for republican government,” then gained control of the legislature, “overwhelming by their majorities the honest & enlightened patriots…”

Their pockets filled with British gold, these paid agents “intrigued themselves into the municipality of Paris,” said Jefferson, “controlled by terrorism the proceedings of the legislature…” and finally “murdered the king,” thus “demolishing liberty and government with it.”

In the same letter, Jefferson accused Danton and Marat by name of being on the British payroll.

The London Revolution Society

Jefferson’s views find unexpected support from U.S. historian Micah Alpaugh, who has revealed the extensive influence British reformers exerted over the French revolutionaries. Unlike Jefferson, Alpaugh sees nothing nefarious in this influence, but nonetheless remarks on its surprising extent.

In his 2014 paper, “The British Origins of the French Jacobins,” Alpaugh notes that France’s radical Jacobin clubs were consciously modeled after an existing British organization, the London Revolution Society.(64)

This was a group of English intellectuals who began meeting at the London Tavern in Bishopsgate in 1788, ostensibly to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of William III’s Glorious Revolution. It soon became clear, however, that their true goal was to agitate for revolution in the present day.

On November 25, 1789—four months after the storming of the Bastille—King Louis XVI was still on his throne, showing every willingness to work with the new National Assembly to form a constitutional monarchy.

Sadly for Louis—and for all of France—events took a fateful turn that day which would end all possibility of cooperation. The catalyst for this catastrophe was a letter from the London Revolution Society to the French National Assembly.

British Radicals Intervene

That day, November 25, 1789, the president of the French National Assembly read aloud to the legislators a letter from the London radicals.

The letter directly inspired the formation of the so-called Jacobin clubs, from which Danton, Marat, Robespierre, and the Reign of Terror would later emerge.

The letter called on the French to disdain “National partialities” and join with their English brethren in a revolution that would make “the World free and happy.”

Alpaugh writes that the letter “produced a ‘great sensation’ and loud applause in the Assembly, which wrote back to London declaring how it had seen ‘the aurora of the beautiful day’ when the two nations could put aside their differences and ‘contract an intimate liaison by the similarity of their opinions, and by their common enthusiasm for liberty’.”

This letter fueled a “growing Anglophilia” (Alpaugh’s words), inspiring the French revolutionaries to found a Societé de la Révolution, directly modeled after the London Revolution Society.

The Societé de la Révolution was later renamed, but always kept its English-style nickname Club des Jacobins—pointedly retaining the English word “club” as a tribute to the group’s British origin, Alpaugh explains.(65)

The Poisoned Chalice

As Jacobin “clubs” sprang up all over France, they typically retained close ties to their English mentors.

Alpaugh writes, “Early French Jacobins created their network in consultation with British models,” such as the London Revolution Society and the London Corresponding Society. “Direct correspondence between British and French radical organizations between 1787 and 1793 would develop reciprocal and mutually inspiring relationships…helping inspire the rise of Jacobin Clubs throughout France,” writes Alpaugh.(66)

Deliberately or not, the so-called “English Jacobins” (as they came to be known) offered their French disciples a poisoned chalice of “cosmopolitanism, internationalism, and universalism” (Alpaugh’s words), urging the French idealists to put aside the narrow interests of their own country, in favor of the broader interests of mankind.(67)

This was, in fact, a deception.

Alpaugh may not see it this way, but the broader interests of mankind pushed by the “English Jacobins” turned out to be little more than a smokescreen for British imperial interests.

The Jacobin Clubs gave rise to Marat, Danton, and Robespierre, ultimately leading to the Reign of Terror and the murder of King Louis XVI.

They also gave rise to a new ideology which has come to be known as communism.

The Invention of Communism

Communism was born on the streets of revolutionary Paris.

More than fifty years before Marx and Engels penned The Communist Manifesto, a faction of French radicals calling itself the Conspiracy of Equals was already preaching classless society, abolition of private property, and the need for revolutionary action.

Led by “Gracchus” Babeuf—whose real name was François-Noël Babeuf—the Conspiracy of Equals tried unsuccessfully to overthrow the so-called Directory, France’s last revolutionary government, in 1796.(68)

Their conspiracy failed, and Babeuf was put to death. But his ideas live on.

Marx and Engels called Babeuf the first modern communist.(69)

No record exists of Babeuf using the word communiste, though he sometimes called his followers “communautistes” (usually translated “communitarian”).(70)

However, a contemporary of Babeuf, Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne, often used the word “communist” in his writings, beginning as early as 1785.(71)

Babeuf’s prosecutors apparently believed that Restif was secretly in league with the Conspiracy of Equals, and some evidence suggests he may have been, according to James Billington, in his 1980 book Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith.(72)

Jacobin Communism

For all these reasons, it is not surprising that the self-styled “communistes” who emerged in Paris during the 1830s and 1840s saw themselves, at least partly, as following in the footsteps of Babeuf.(73)

“The term ‘communism’ in the France of the 1840s denoted… an offshoot of the Jacobin tradition of the first French revolution,” wrote Marxist historian David Fernbach in 1973. “This communism went back to Gracchus Babeuf’s Conspiracy of Equals… This egalitarian or ‘crude’ communism, as Marx called it originated before the great development of machine industry. It appealed to the Paris sans-culottes—artisans, journeymen and unemployed—and potentially to the poor peasantry in the countryside.”(74)

Thus, Babeuf’s “crude” communism was already shaking up Paris more than 20 years before Marx was born.

By March, 1840, the Communist movement in Paris was deemed sufficiently threatening that a German newspaper denounced it, saying, “The Communists have in view nothing less than a levelling of society— substituting for the presently-existing order of things the absurd, immoral and impossible utopia of a community of goods.”(75)

When these words were written, the 21-year-old Karl Marx was studying classics and philosophy in Berlin. He had not yet shown a strong interest in radical or revolutionary politics.

Babeuf’s British Mentors

Babeuf’s status as the founding father of communism cannot be disputed.

It is therefore significant that Babeuf derived many of his ideas from British mentors, at least some of whom were British intelligence operatives. In that respect, Babeuf followed a path trod by many other French revolutionaries.

One of Babeuf’s mentors was James Rutledge, an Englishman living in Paris, who called himself a “citizen of the universe” and preached the abolition of private ownership.(76) “Babeuf had known Rutledge even before the revolution,” writes Billington in Fire in the Minds of Men (1980).

Through Rutledge and his circle, Babeuf became acquainted with the Courrier de l’Europe, a French-language newspaper published in London and distributed in France. It promoted such radical doctrines as the overthrow of the French aristocracy and the establishment of a classless society. Babeuf became a regular correspondent of the paper in 1789.(77)

It appears to have been a British intelligence front.

The newspaper’s owner was London wine merchant Samuel Swinton, a former lieutenant in the Royal Navy who had, in the past, performed sensitive diplomatic missions for Prime Minister Lord North.

In a 1985 paper, French historian Hélène Maspero Clerc concluded that Swinton was a British secret agent, based upon her study of Swinton’s correspondence with British Secretary of the Admiralty Philip Stephens.(78)

Was Marx a British Agent of Influence?

In some respects, Karl Marx’s career followed a trajectory similar to that of the French revolutionaries. Like them, Marx was influenced by British mentors, at least some of whom are known to have been intelligence operatives.

In Marx’s case, the British influence was arguably stronger than it had been with Babeuf.

For one thing, Marx had family connections to the British aristocracy.

In 1843, he married Jenny von Westphalen. Her father was a Prussian baron, whose Scottish mother, Jeanie Wishart, descended from the Earls of Argyll.(79)

In 1847, Marx and Engels were commissioned by the London-based Communist League to write the Communist Manifesto. The tract was published first in London, in 1848.(80)

Expelled from Prussia, France, and Belgium for his subversive activities, Marx and his family took refuge in England in 1849. He lived in London for the rest of his life.

Karl Marx: Imperial Propagandist

In February, 1854, Marx met Scottish nobleman David Urquhart (pronounced ERK-art)— apparently a distant relative of Marx’s wife, through her Scottish grandmother.(81)

Urquhart was a British diplomat and sometime secret agent, who became something of a 19th-century Lawrence of Arabia.

After fighting in the Greek War of Independence, Urquhart served as a diplomat in Constantinople, where he became a close confidant of the Sultan. In 1834, Urquhart instigated a rebellion against Russia among the Circassian tribes of the Caucasus. The Circassians named him Daud Bey (Chief David), a name by which he became famous throughout the Middle East.(82)

Urquhart had a fanatical hatred of Russia, so intense that he publicly accused Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, of being a paid Russian agent.(83)

Somewhat surprisingly, Marx joined Urquhart’s cause, becoming one of the most prominent anti-Russian journalists of his day. Marx wrote blistering anti-Russian screeds for The New York Tribune—then the highest-circulation newspaper in the world—as well as for Urquhart’s own publications in Britain.(84)

Marx went so far as to echo Urquhart’s accusation that Lord Palmerston was secretly in league with the Russians.(85)

In his attacks on Russia, Marx wrote not as a revolutionary, but as a propagandist for British imperial interests. His tirades against Russia proved useful to the Empire during the Crimean War of 1853-1856.

“The Revolutionist and the Reactionary”

The alliance between Marx and Urquhart has confounded historians for generations.

Marx was a communist, and Urquhart an arch-reactionary.

What bound them together? What could they possibly have had in common?

Many scholars have simply ignored this question. Some have actively tried to suppress it, by concealing the very existence of Marx’s anti-Russian work.

In his 1999 biography Karl Marx: A Life, Francis Wheen writes:

“His [Marx’s] philippics against Palmerston and Russia were reissued in 1899 by his daughter Eleanor as two pamphlets, The Secret Diplomatic History of the Eighteenth Century and The Story of the Life of Lord Palmerston—though with some of the more provocative passages quietly excised. For most of the twentieth century they remained out of print and largely forgotten. The Institute of Marxism-Leninism in Moscow omitted them from its otherwise exhaustive Collected Works, presumably because the Soviet editors could not bring themselves to admit that the presiding spirit of the Russian revolution had in fact been a fervent Russophobe. Marxist hagiographers in the West have also been reluctant to draw attention to this embarrassing partnership between the revolutionist and the reactionary. An all-too-typical example is The Life and Teaching of Karl Marx by John Lewis, published in 1965; the curious reader may search the text for any mention of David Urquhart, or of Marx’s contribution to his obsessive crusade but will find nothing.”(86)

“Kindred Souls”

In his 1910 biography, Karl Marx: His Life and Work, John Spargo argues that, “Marx gladly cooperated with David Urquhart and his followers in their anti-Russian campaign, for he regarded Russia as the leading reactionary Power in the world, and never lost an opportunity of expressing his hatred of it.”(87)

Spargo thus tries to explain Marx’s anti-Russian work in terms of an ideological aversion to Russia’s “reactionary” politics, which is to say, Russia’s feudal condition during the 1850s, whereby the Tsar held absolute power, and the landowning nobility kept more than 20 million peasants in a state of serfdom.

This interpretation does not pass muster, however.

In all of Britain, there was no more “reactionary” voice than David Urquhart, who openly called for a restoration of the feudal system.

In his 1845 book Wealth and Want, Urquhart argued that a serf under feudalism was better off than the paupers, miners, and factory workers of the present industrial age.(88)

“Serfdom, I assert, to have been a better condition than dependent labour…” Urquhart wrote. “The villain was not the slave of the lord, but… a freer man than any labourer to-day.”

If Marx hated reaction, why then was he drawn to David Urquhart, whose “reactionary” views surely rivaled those of the most retrograde Russian landlord?

John Spargo writes: “In David Urquhart he [Marx] found a kindred soul to whom he became greatly attached. . . . The influence which David Urquhart obtained over Marx was remarkable. Marx probably never relied upon the judgment of another man as he did upon that of Urquhart.”(89)

The alliance between Marx and Urquhart confronts us with a genuine mystery. If it is true that Marx found a “kindred soul” in Urquhart, then their views must have converged, in ways beyond the obvious. What exactly did these men have in common?

Hatred of the Middle Class

I believe what bonded Marx and Urquhart was their mutual hatred of the middle class.

Urquhart was a leading voice of Young England, a movement of landed aristocrats calling for a return to the feudal system.(90)

The Industrial Revolution had turned British society upside down, forcing men, women, and children of the lower classes to toil long hours in mines and factories under appalling conditions and for meager pay.

The aristocrats of Young England blamed these abuses on the vulgar, money-grubbing culture of the middle class or bourgeoisie.

Things had been better in the Middle Ages, the Young Englanders argued. In those days, benevolent landlords cared for their serfs, as lovingly as they cared for their hounds and horses, never letting them go hungry or homeless.

The problem of “pauperism” would vanish, said the Young Englanders, if the landowning gentry were put back in charge. The aristocrat’s ancient sense of noblesse oblige would motivate blue-bloods to provide for the poor, just as they always had in the past.

“Extinguish the predominance of the middle-class bourgeoisie”

To prove their point, the aristocrats of Young England became reformers in the 1840s, agitating for a ten-hour work day and other policies to help the poor and working class.

To achieve these ends, the Young Englanders allied themselves with communists and socialists, who hated the “bourgeoisie” as much as they did, albeit for different reasons.(91)

The 1902 Encyclopedia Britannica states that the Young England movement, “sought to extinguish the predominance of the middle-class bourgeoisie [emphasis added], and to recreate the political prestige of the aristocracy by resolutely proving its capacity to ameliorate the social, intellectual, and material condition of the peasantry and the labouring classes.”(92)

The key phrase here is “extinguish the predominance of the middle-class bourgeoisie”—a goal the Young Englanders shared with their communist and socialist allies.

Thus the Young England movement brought Tory aristocrats such as Lord John Manners and George Smythe into alliance with socialist firebrands such as Robert Owen and Joseph Rayner Stephens.(93)

Ultimately, it would bring David Urquhart into alliance with Karl Marx.

“Natural Alliance”

The Anglo-Irish writer Kenelm Henry Digby has been widely acknowledged as the spiritual leader of Young England.

His trilogy The Broad Stone of Honour—written between 1829 and 1848—served as the movement’s “handbook” or “breviary” (prayerbook), according to Charles Whibley’s 1925 history of the movement, Lord John Manners and His Friends.(94)

Whibley writes: “And he [Digby] found in the champions of Young England his most willing pupils, because… he admitted that the aristocracy and the people formed a natural alliance…”

Regarding this “natural alliance” between nobility and peasantry, Whibley quotes Digby as follows: “I pronounce that there is ever a peculiar connection, a sympathy of feeling and affection, a kind of fellowship which is instantly felt and recognised by both, between these [the lower classes] and the highest order, that of gentlemen. In society, as in the atmosphere of the world, it is the middle which is the region of disorder and confusion and tempest [emphasis added].’”(95)

By “the middle,” Digby plainly means the “middle class.”

Like Marx, Digby saw the bourgeoisie as a disturbing new force in the world, breaking the old “natural alliance” between lord and serf, and sowing “disorder,” “confusion” and “tempest.”

Marx may or may not have read Digby, but his view of the middle class is undeniably Digby-esque.

The Myth of the Bourgeois Revolution

“It is not the abolition of property generally which distinguishes Communism; It is the abolition of Bourgeois property,” wrote Marx in The Communist Manifesto (1848).(96)

By distinguishing between “bourgeois property” and “property generally” Marx meant that his new Communist movement would not focus on fighting the landowning gentry because—according to Marx—that battle had already been won.

The real power in today’s world, Marx insisted, was no longer the feudal lord, but the bourgeois businessman, who had supposedly overthrown the aristocrats in a series of bourgeois revolutions.

That is why we are now asked to believe that self-made entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk are the richest, most powerful men on earth.

In reality, we have no way of knowing who the wealthiest people are, as wealth is routinely hidden in offshore trusts, beneath layers of shell corporations, where it cannot be traced.

There are, in fact, indications—contrary to Marx’s theory of bourgeois revolution—that certain aristocratic families not only managed to survive the Industrial Revolution with their wealth and power intact, but learned to thrive in the new system, living quietly, out of sight, and letting the bourgeoisie get all the limelight.

The Persistent Power of the Aristocracy

More than 70 years after Marx and Engels pronounced the feudal aristocracy dead, the power of Britain’s landed nobility emerged unexpectedly as a topic of heated debate in the U.S. Senate.

In 1919, the Senate was pondering the question of whether or not to ratify the Versailles Treaty, which would have required the US to join the League of Nations. Public opinion ran strongly against ratification, as most Americans—not unreasonably—feared the League of Nations would draw the US back into a dependent relationship with the British Empire.

Daniel F. Cohalan, a justice of the New York Supreme Court, appeared before the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee on August 30, 1919, to argue against ratification.

Born in New York, of Irish descent, Cohalan was active in the Irish Republican movement. He claimed to speak for America’s 20 million citizens of Irish descent, which is to say, for one in five Americans alive at that time.(97)

“We believe we went to war for the purpose of ending autocracy… ,” Cohalan told the Foreign Affairs Committee.(98) Yet the British Empire represented, “the most absolute, most arbitrary and most powerful autocracy the world has ever seen,” he declared.(99)

Cohalan’s testimony on this point is worth quoting at length.

“[T]he real ruling force is… the landed feudal aristocracy of England…”

Justice Cohalan told the U.S. Senate:

“The ordinary American… has not come to understand that the English democracy of which he hears and reads so much has little reality in fact, and that England continues to be governed by a handful of men, representing, with but few exceptions, the same small group of titled land-controlling families that have governed England since the days of Henry VIII, if not, in fact, much longer. …

“The dominating figures in England to-day—those in actual power—are the Cecils and their relations [emphasis added]. Lloyd-George or some other figure that has come to represent democracy… is put forward as the premier of governing authority. But the will that dominates, controls, and finally directs the policies and actions of England is that of the master spirit Cecil, no matter which member of that family or its connections it may happen to be. …

“Englishmen like to say that King George reigns but does not rule. That is true. The real ruling force is that handful of aristocrats who represent the landed feudal aristocracy of England and who form the most absolute, most arbitrary and most powerful autocracy the world has ever seen.”(100)

This is not the place to debate the question of who really runs things in this world, but Judge Cohalan’s testimony at least reminds us that the obvious and familiar answers are not necessarily the right ones.

The “Naked, Shameless, Brutal” Bourgeoisie

Like his aristocratic mentor Urquhart, Marx had a tendency to romanticize the “idyllic” feudal past, and to vilify middle-class culture, in terms reminiscent of the Young Englanders.

That is not to say that Marx was blind to feudal injustice and inequality. But Marx plainly saw the bourgeois order as worse.

Marx imagined the Middle Ages as offering, at the very least, some comforting illusion of a harmonious natural order, based on “patriarchal” relations, chivalry, and faith.

The money-grubbing bourgeoisie, on the other hand, had stripped away those illusions, leaving only “naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation,” said Marx.

Marx spelled it out in the Communist Manifesto. He wrote: “The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors’, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.”(101)

Digby himself could not have said it better.

Young England Lives On

Most historians hold that the Young England movement petered out around 1849.

Yet the spirit of Young England lived on, under different guises.

It survived through the strange, symbiotic relationship between Urquhart and Marx.

It lingered, through the 1880s, in the teachings of Oxford professor John Ruskin, and two of his young disciples, Arnold Toynbee and Alfred Milner.(102)

The Ruskinites embraced a philosophy that would one day come to be known as “liberal imperialism”—the notion that the best way to spread enlightened social policies across the world was by conquest and colonization, that is, through expansion of the British Empire.

Milner would go on to become one of Britain’s leading statesmen. He served as colonial governor of southern Africa during the Boer Wars, and as War Secretary for Lloyd George during World War I.

In 1920, the deposed premier of Russia, Alexander Kerensky, would call Milner the “wicked genius of Russia,” a reference to Milner’s controversial role in stirring up the Russian Revolution.(103)

But that’s getting ahead of our story.

How Marxism Serves the Empire

In 1882, Milner was just an idealistic young journalist filled with enthusiasm for imperialism and social reform.

In that year—the last year of Marx’s life—Toynbee and Milner both gave lecture series on the topic of socialism.(104)

Both praised Marx as a genius. Both argued, intriguingly, that socialism was Britain’s secret weapon for containing and heading off revolution.

The core of their argument was pure Young Englandism—the idea that the upper classes could save Britain from revolution by giving socialism to the masses.

They further claimed—once again in the spirit of Young England—that the middle class, or bourgeoisie, was the biggest obstacle to their goal.

These 1882 lectures of Toynbee and Milner were so similar in form and subject matter that I will quote from them below, alternately allowing Toynbee and Milner to complete each other’s thoughts.

Heading off Revolution

Milner began by acknowledging Marx’s core argument that the Industrial Revolution had intensified class conflict to the point that revolution was imminent.

However, England could escape revolution if she acted wisely, said Milner.

“The industrial revolution in England is the type and forerunner of that which has swept over every country in Europe,” Milner said. “We got through it sooner, we experienced its evils sooner, perhaps we shall find hereafter that we have begun to discover the remedies for these evils sooner than any other nation.”(105)

And what were those remedies? “Socialist programmes,” said Toynbee.(106)

Toynbee argued that, of all countries, England was least likely to experience a revolution, because she had had the foresight to implement “socialist programmes” before it was too late.

“Some of the things the Socialists of Germany and France are now working for, we have had since 1834,” Toynbee boasted. In this regard, Toynbee cited the New Poor Law of 1834, which had established workhouses for the poor, and the various Factory Acts, such as those of 1847 and 1848, which had established a 10-hour work day as well as other improvements in work conditions.

Such measures, said Toynbee, had “saved England from revolution.”

The Bourgeois Threat

Toynbee expressly credited the Young England movement for these enlightened policies, praising Lord John Manners by name.

“[L]et us recognize the fact plainly,” said Toynbee, “that it is because there has been a ruling aristocracy in England that we have had a great Socialist programme carried out. … [T]he supremacy of the landowners, which has been the cause of so much injustice and suffering, has also been the means of averting revolution.”(107)

Milner and Toynbee both agreed that the best way to head off revolution was by meeting the revolutionaries halfway and giving them some form of socialism.

Like the Young Englanders before them, Milner and Toynbee recognized a “natural alliance” between the upper and lower classes. It was the middle class, the bourgeoisie, that posed a problem.

Milner pointed squarely to the middle class as the greatest threat to social stability.

He condemned what he called, “the dominant principles of economics, the middle-class or bourgeois principles which have been invented by Capitalists to justify the Capitalistic system and to maintain it.”(108)

Communism: “The Ultimate Form of Human Society”

Milner continued: “The fundamental doctrine of the dominant [middle-class] school—and on reflection I think the Socialists are justified in calling it dominant, it is dominant in Parliament, in the Press, in nine-tenths of our laws and institutions… the doctrine of this dominant bourgeois or middle-class economy is that the whole business of the State is to protect the personal freedom and the property of the individual.”(109)

However, Milner saw a new order on the horizon, one in which the “bourgeois or middle-class” values of “personal freedom” and “property” would no longer dominate men’s thinking.

“I don’t deny that Communism may be the ultimate form of human society,” Milner stated, though he allowed that “pure Communism” might be “impracticable” for the present age.(110)

Impractical or not, Milner had high praise for Karl Marx.

In an 1882 lecture on the “German Socialists,” Milner called Marx, “one of the most weighty, logical and learned of reasoners,” adding, “Marx’s great book Das Kapital is at once a monument of reasoning and a storehouse of facts.”(111)

Milner’s Ultimatum to the Tsar